As outlined in WYSE Travel Confederation’s New Horizons IV: A global study of the youth and student traveller, the rise of the digital nomad was already evident, even before the pandemic. In New Horizons IV we analysed the profile of those youth travellers who identified themselves as digital nomads, who we defined as “Travellers who use digital technologies to work and/or support a location-independent lifestyle.”

At that time in 2017, digital nomads appeared as a small but interesting youth travel niche market. On the basis of our research we estimated that around 1.8 million youth travellers globally would identify themselves as digital nomads. Although this seemed like a small niche at the time, digital nomads are important because of the influence they have on other young travellers through blogging, travel advice and other influencer activities promoting their apparently desirable lifestyle. Many digital nomads are busy selling this travel style to others as a means of supporting their own travel lifestyle. Pieter Levels’ Nomad List is one example.

Based on the New Horizons research, we concluded “Digital nomads will become an important segment of youth travellers as location-independent work and related travel increase. Demand for co-working space, flexible accommodation and other travel provisions for proto-locals will grow.” We hate to say “we told you so”, but the COVID-19 pandemic certainly made sure we were right.

Before the pandemic, the New Horizons research indicated that digital nomads were likely to spend almost half of their travel time in large and gateway cities. This has almost certainly changed in recent years, but we will have to wait for the results of the 2023 New Horizons survey to find out. What is clear is that many destinations have now jumped on the digital nomad bandwagon. There has been a marked growth in countries offering digital nomad visas, and the pace of growth has quickened since the pandemic. In addition, many youth tourism suppliers are now catering to this market, providing long-term accommodation and co-working facilities to attract location-independent workers. One survey estimated that there were 13,800 co-working spaces worldwide in 2017 with 1,180,000 members (Social Workplaces, 2017). By 2022, Statistia estimated that there were 23,500 co-working spaces with 4.3 million members, almost triple the pre-pandemic level.

The origin of digital nomadism lies in an increasing desire for the freedom and flexibility of location-independent work. Being a digital nomad is also a useful way to cover the costs of travel without having to visit one a traditional ‘work and travel’ destinations, such as Australia, the USA or Canada. A Gallup survey found that “43% of employed Americans spent at least some time working remotely” in 2016, and this continued to increase after the pandemic. Young people in particular have become “asset-light” and can travel widely unfettered by mortgages or personal ties. Our 2017 New Horizons research showed that digital nomads manage their location independence by making extensive use of Airbnb (56% used on their last main trip abroad). Digital nomads are potentially interesting for suppliers and destinations because of their relatively high spend. However, in some destinations there is growing criticism of digital nomad arrivals, who are sometimes seen as having a negative impact on local communities and pushing up housing prices (Ferreira, 2022).

Our New Horizons IV findings suggested that destinations could position themselves for the digital nomad market by easing visa requirements and allowing digital nomads to stay for longer periods. Based on our survey, a typical digital nomad travelled for 50 days in 2017.

Growing digital nomad demand

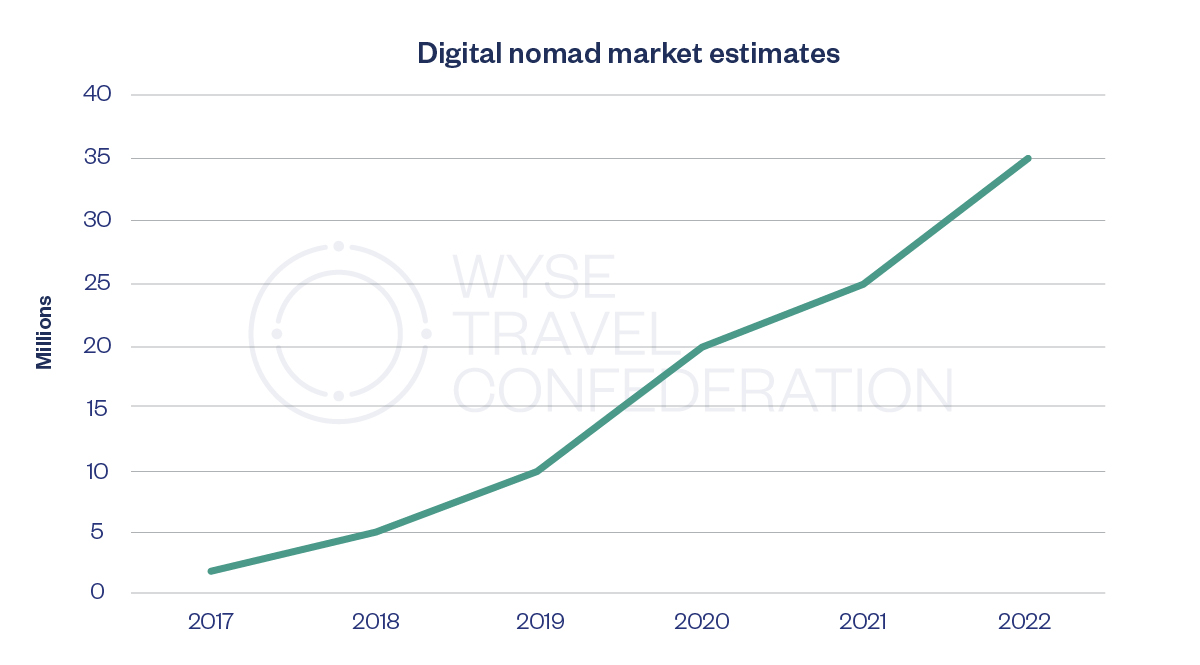

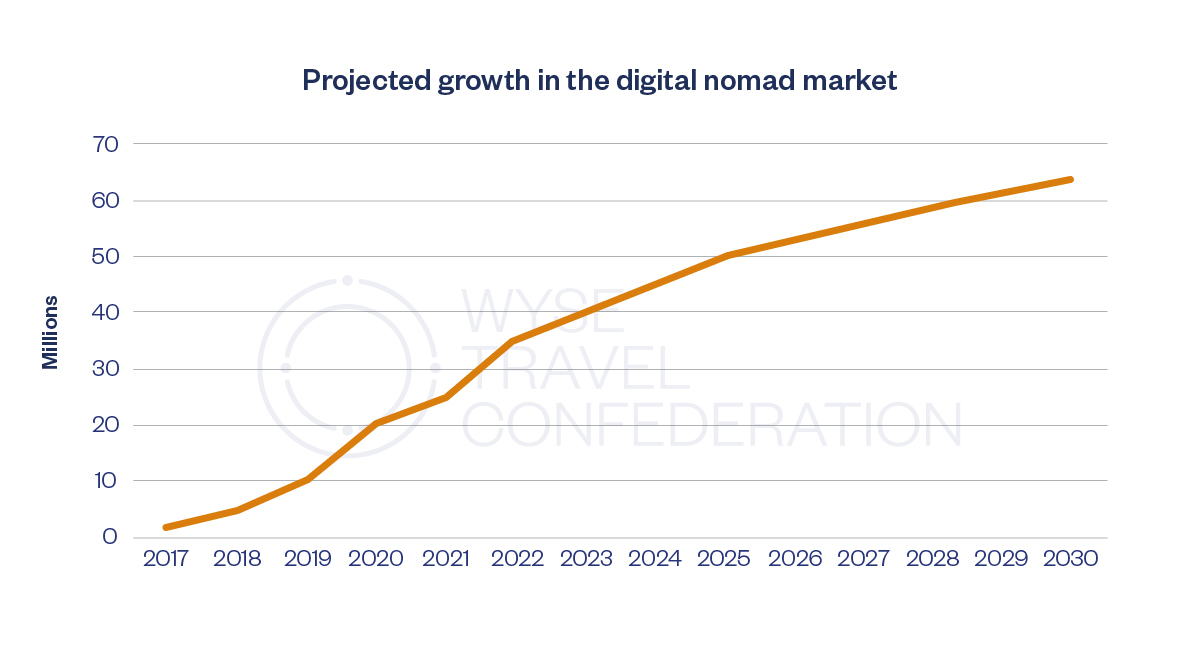

The 2017 New Horizons IV survey provided us with an initial estimate of a total of 1.8 million youth traveller digital nomads worldwide. Since then, other studies have indicated a steady growth in the total digital nomad market, to around 35 million in 2022. Given that Millennials and Gen Z account for around 70% of digital nomads, that indicates a current global potential market of around 24 million.

Sources: New Horizons IV: A global study of youth and student travel, 2017, MBO Partners (2020), A Brother Abroad (2022).

The MBO digital nomad report indicated a sharp growth in the US, with a 50% growth between 2019 and 2020. The research also found digital nomads were becoming younger, with an increase of Gen Z and Millennials, who together accounted for 62 percent of the market. The Coworking Survey Europe also found that co-working spaces expected future growth. Two thirds of survey respondents expected more digital nomads compared to before the pandemic, and half expected more demand for workstations. In Europe, there was also evidence of digital nomad travel increases during the pandemic, with the Canary Islands reporting a 10% growth at the height of travel restrictions, and a 67% increase in 2021, after restrictions had been lifted (Parreño-Castellano Domínguez-Mujica & Moreno-Medina, 2022).

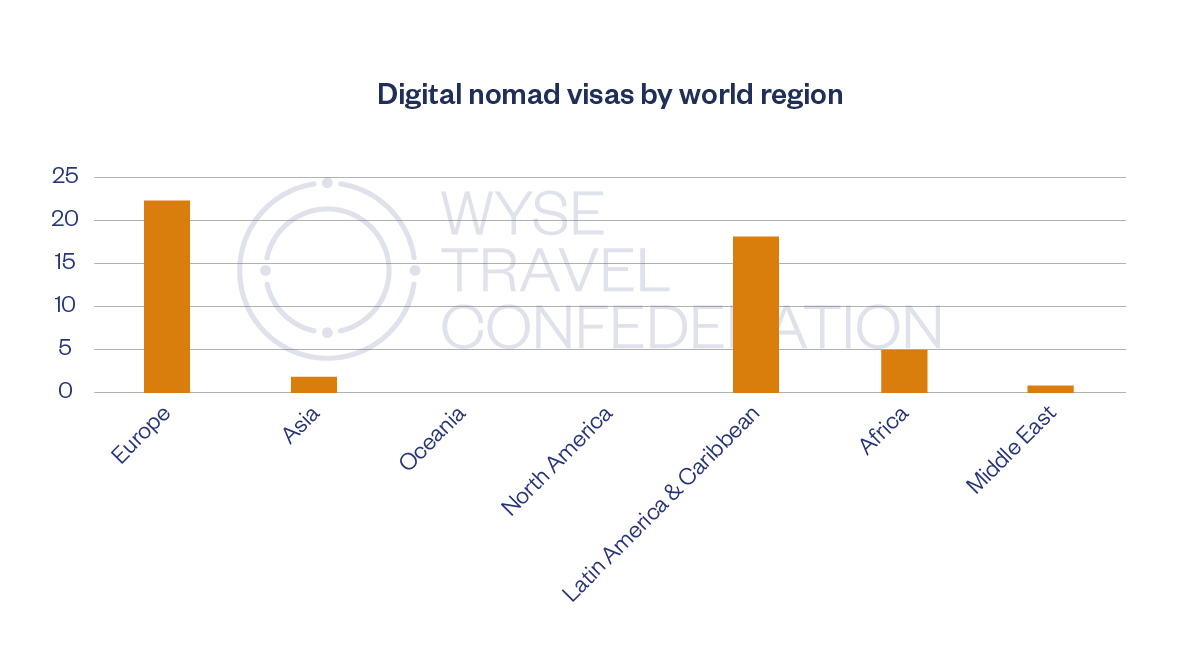

Many destinations seem to have heeded our call to cater for digital nomads, particularly following the COVID-19 pandemic. Our review of digital nomad visas shows that there are now 50 plus countries offering targeted visas. Most of these countries are located in Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean. To date, countries such as Australia, Canada and the USA have not opened up to the digital nomad market, arguably because they already have well-established work and travel schemes as well as highly structured immigration programmes.

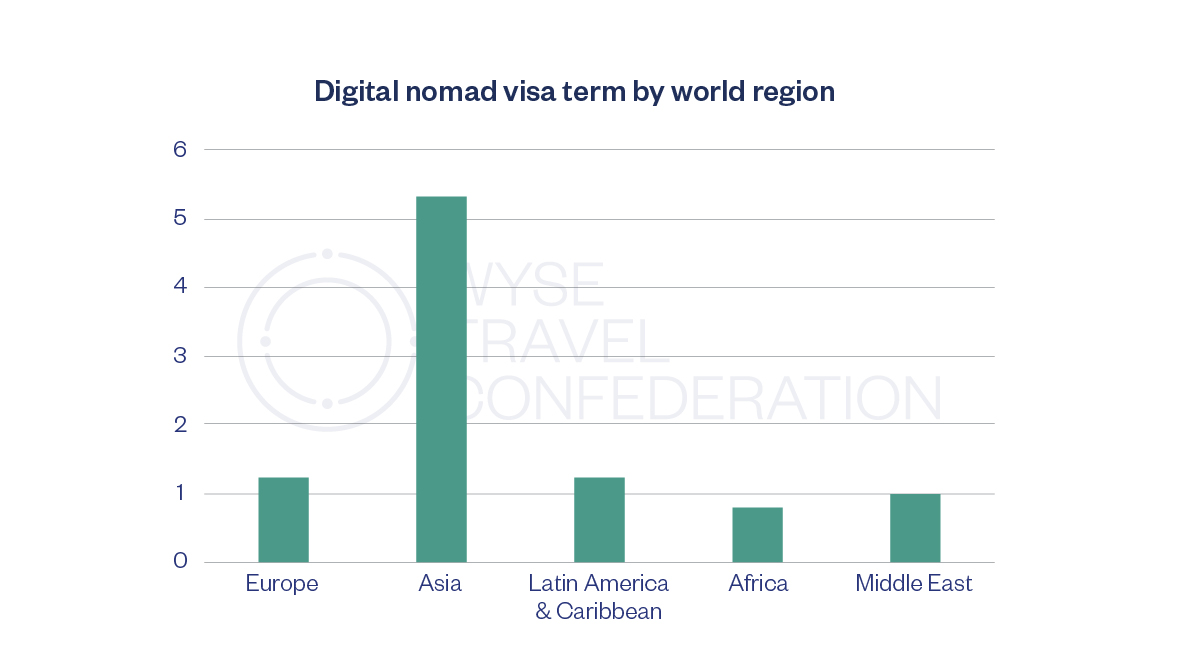

The vast majority of digital nomad visas are offered for one year or less, with only a handful of countries offering more than a year. The major exception to this is Thailand, which is introducing a visa with a maximum term of 10 years. However, the requirements for this visa, such as having earned USD 80,000 in the previous two years or having USD1 million in the bank, indicate that this visa is not aimed at young travellers.

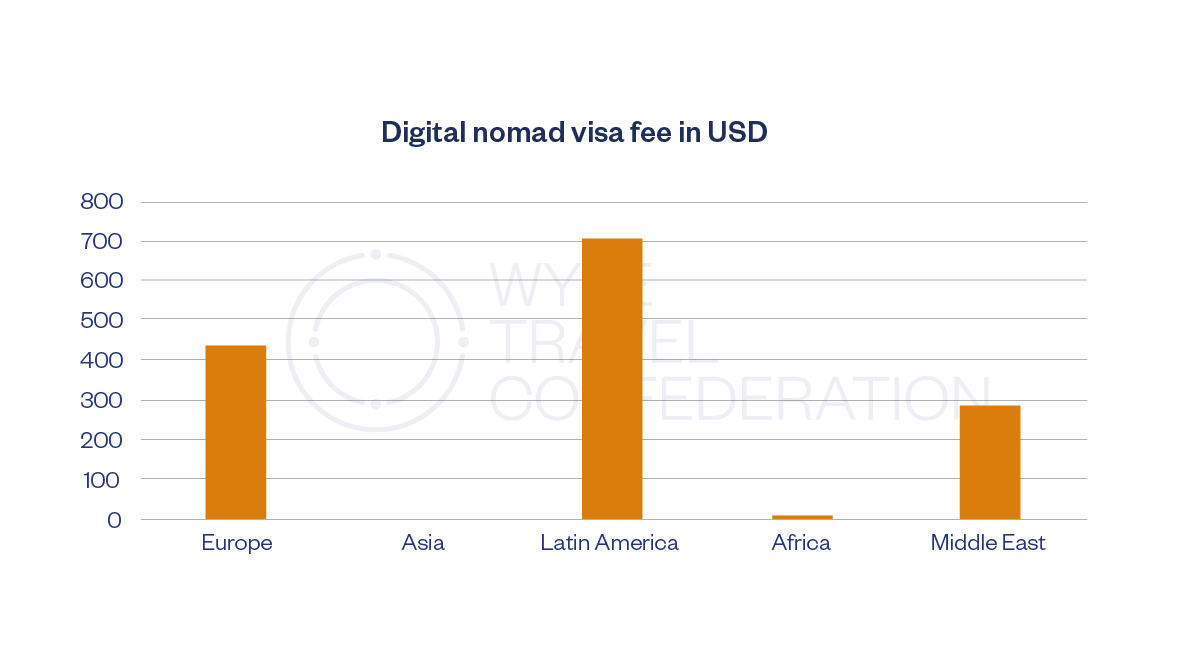

The average visa fee is around USD 500, but there are considerable variations. In general, Caribbean islands have the most expensive fees, with Barbados and Anguilla both charging USD 2000.

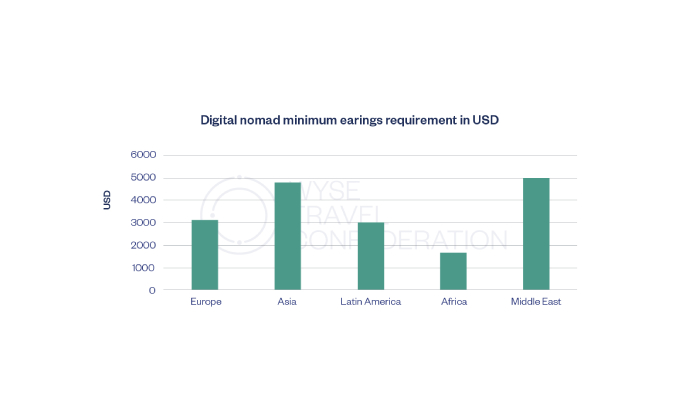

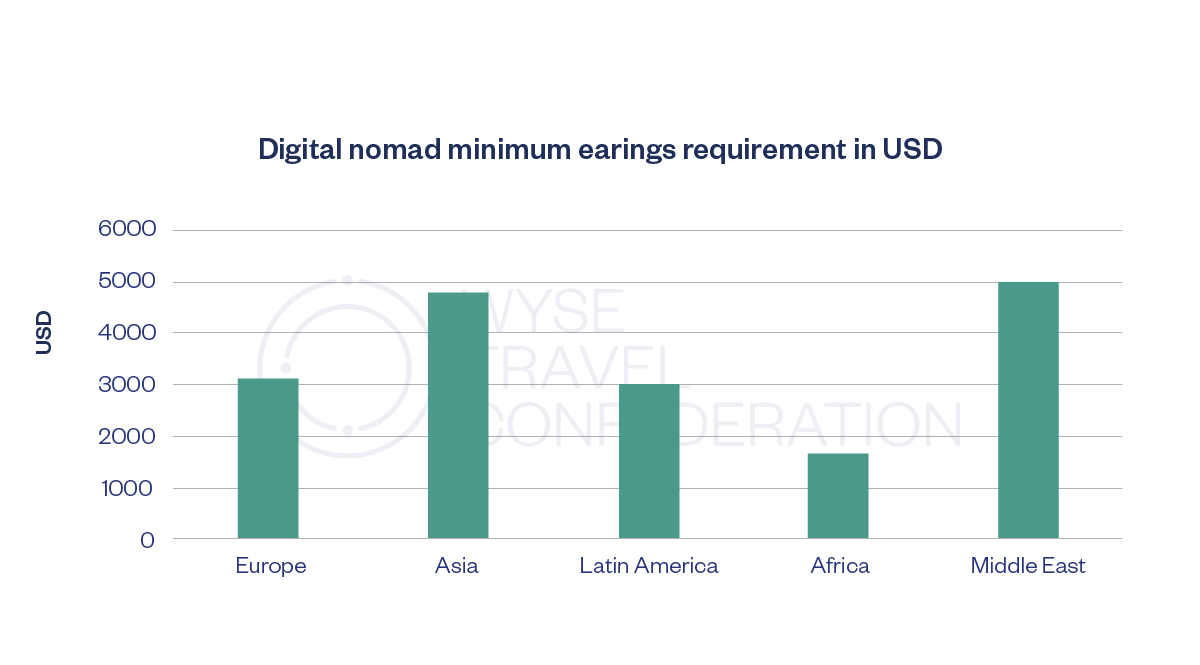

Most countries also have a minimum earnings requirement. The average is around USD 3000 a month, but some countries require substantially more. The Cayman Islands asks for USD 100,000, and Belize wants USD 80,000. But there are also a number of countries that have no earnings requirement, including South Africa and Spain.

A number of European countries also position their digital nomad visas as a gateway to the Schengen Area of the European Union, allowing visa-free travel across many countries.

The growth in digital nomad visas indicates that many countries have responded to the increased demand for location-independent working. This has been particularly evident since the pandemic, as most visas have been developed since 2020.

Future trends

In America, the MBO Partners 2020 State of Independence report found that 17 million people in the USA want to be digital nomads in the near future, or a growth of over 50% compared with 2020. Taking this evidence, together with the growth trajectory of recent market estimates, we expect the global number of digital nomads to top 40 million this year, with the market slowly maturing to reach around 60 million by 2030. This is still a long way off Pieter Levels’ estimate of 1 billion digital nomads by 2035, but a big market nonetheless!

This growth provides a number of potential new opportunities for the youth travel sector, as we outlined in WYSE Travel Confederation’s “Digital nomads: From the margins to the mainstream?” presentation at WYSTC 2020. These include growing demand for hostel accommodation, particularly as a landing pad for digital nomads looking to test the water in new destinations. Some operators, notably Selina, have been moving in this direction during the pandemic, offering deals on longer stays and boosting co-working facilities. Where digital nomads decide to stay for longer periods, we are also likely to see a growing demand for ‘co-living’ facilities. Some destinations, such as Madeira in Portugal, have already begun to develop hubs to attract digital nomads to congregate and settle for long periods. In these destinations there will also be growing demand for events and services aimed at digital nomads, and they will also need services such as insurance and visa assistance.

References

A Brother Abroad (2022). 63 Surprising Digital Nomad Statistics. https://abrotherabroad.com/digital-nomad-statistics/

Ferreira, S. (2022). Welcome to Digital Nomadland. Wired, December 16, 2022.

MBO Partners (2020). COVID-19 and the Rise of the Digital Nomad – The MBO Partners’ 2020 State of Independence Report.

WYSE Travel Confederation (2017). New Horizons IV: A global study of the youth and student traveller, “Gone digi-nomad: Tracking the unwired traveller”

Parreño-Castellano, J., Domínguez-Mujica, J. & Moreno-Medina, C. (2022). Reflections on Digital Nomadism in Spain during the COVID-19 Pandemic—Effect of Policy and Place. Sustainability, 14(6), December 2022.

Social Workplaces (2017). 2017 Global Coworking Survey. SocialWorkplaces.com.

|

Author Prof. Greg Richards, Professor of Placemaking and Events Breda University of Applied Sciences |